Analog Pasts and Futures: Philadelphia as a Case Study

By Andi Avery

This article is part of the Analog Futures issue of Analog Cookbook. Available now.

Supplemental readings provided by the author

California’s Long “War of Extermination”

Hundreds call for reckoning with American artist Thomas Eakins’s troubling legacy

In thinking about the theme of analog futures for this issue, it occurred to me that one of the ways to discern what is wanted and needed for the future is to think about the past. As I type this, I am sitting in my studio in Philadelphia, a city that has an incredibly complicated history with photography, specifically. When we’re looking at some of the biggest names in Philly’s photographic history, we’re looking at art that was funded by historical figures famous for the exploitation of BIPOC folks. This year, we’ve seen multiple, massive city institutions get called out for exploitative collection and display practices. In a city that is predominantly populated by People of Color, it feels especially important to talk about institutional access for our future. At the moment, Philadelphia’s more prominent institutions are taking strides, but largely struggling to meet the moment.

Eadweard Muybridge (you know - the dude with the running horse), conducted many of his motion studies at the University of Pennsylvania right here in the city. The majority of Muybridge’s early motion work was financed by Leland Stanford, a robber baron who was infamous for the exploitation of the Chinese immigrants who built the railroad that made him wealthy, as well as the displacement and murder of thousands of Indigenous people during his time as Governor and during the building of Stanford University on Muwekma-Ohlone land [1]. Muybridge and Stanford met and began working together after Stanford retired and took up horse breeding. Stanford paid Muybridge $50,000 (about 1 million dollars today) to prove that for a fraction of a second while running, horses took all four feet off the ground. You know, because he was curious and had $50,000 to spare. Once he and Stanford parted ways, Muybridge attracted the attention of Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins, who helped him raise money from Philadelphia’s elite to continue his work.

Eakins also created a large portion of his work in Philadelphia - and the city will never let you forget it. Although numerous scholars have written about Eakins’s long history of exploitative behavior including sexual violence and misconduct, that seems to have been forgotten (or, more likely, ignored) by the city. We have an Eakins historical marker in the center of our city, the Eakins Oval (a fittingly stressful traffic circle), and the National Register of Historic Places has certified Eakins’s old house. In 2006, two Philadelphia institutions and numerous funders, including the Pugh Foundation, scrambled to pull together $68 million to keep Eakins’s painting “The Gross Clinic” from leaving the city. Philadelphia’s financially insecure artists are relieved, I’m sure.

2021 brought a bit of a reckoning in the art world, here and elsewhere. Eakins’s personal archive, which contained many photos of nude minors from whom a record of consent by a guardian was not obtained or available, was previously available on the internet without censorship. Local artist Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter, after seeing Eakins’s photos of an anonymous, nude prepubescent Black girl in the collection, created her incredibly poignant piece Consecration to Mary in which she inserted images of herself into Eakins’s photos as a protective and mothering presence to the subject. In an open letter spearheaded by Baxter, over 200 artists added their names to support her request that Philadelphia’s major institutions “formally cease and desist their love affair with Thomas Eakins.”

Why is it so hard to get Philadelphia’s institutions (see also: all institutions, academia, etc.) to acknowledge their own historical bias? The answer is, of course, complicated. Historically, it has been considered objectively good for institutions to collect and store objects. For centuries, artists’ work products have been furiously hoarded for collection and display in institutions that weren’t necessarily accessible. We consider the digitization of archives and work to be positive from an access perspective, but it’s also allowing a lot of work to become public without thought or consideration. It’s becoming increasingly obvious that good stewardship of any collection includes not taking a neutral position, because neutrality around objects that used to cause harm leaves space for them to continue to do so.

In thinking about these parts of our past (accessibility, stewardship, education, and community relationships), it became clear to me that there are smaller, newer institutions that are setting a thoughtful model for what our relationship to art and photography could be.

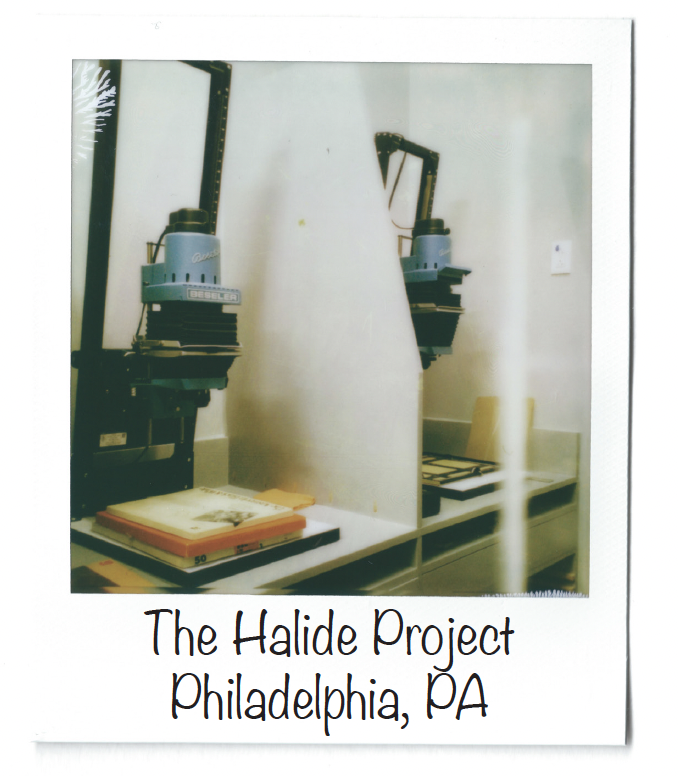

Nestled into Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood exists The Halide Project, Philadelphia’s newest non-profit community darkroom that is set to open its doors any day now. I was able to speak with Dale Rio, a wildly talented film photographer and one of THP’s founding members, who told me that, “one thing that we like to strive for at Halide is creating a welcoming space.” I was able to see the space a week later, and upon taking a tour and meeting a few of the other folks in Halide’s orbit, I can say that portion of their goal was indeed successful.

Among other things, the space features a seven-bay B&W gang darkroom with five Omega D5s and two Beseler 23Cs, a film processing area with both steel and plastic tanks for roll film and tanks for sheet film processing, a lovingly-built four-bay UV exposure unit and dedicated coating area for alternative processes, and a private darkroom with Jobo ATL3 unit for color film and print processing. There is also a fairly large gallery space, which was in transition to a juried show when I stopped by.

One of the things I spoke about with Dale was accessibility, and she was very clear about the fact that the board is in frequent communication around how to equitably accommodate the needs of the community. One of my favorite features of the space was a camera lending library that will be available to all members. The collection is already impressive and still growing. Currently, they are also seeking volunteers, and plan to offer a work-exchange program for darkroom time.

Although the ongoing pandemic dramatically pushed back THP’s opening date, they have had, and continue to have, virtual artists talks that occur every other Monday night, and quarterly group critiques available. These events are on a pay-what-you-wish basis, with a suggested donation of $10. The featured speakers include artists from all over the world, and have served an audience just as broad. The featured speakers include artists who work in palladium, cyanotype, pinhole photography, gum bichromate, multiple exposures, and more. Just as The Halide Project has created a dedicated space for an array of historic and alternative processes, so too have they made a digital space for artists working with historic processes.

When I asked who has shown interest so far, Dale told me that a lot of the folks who expressed interest were adults that had access to a darkroom in college and wanted to come back, and younger folks who found their way to a darkroom through digital work. She also mentioned that often, people just want to dive into a new method or build a new workflow. In stark contrast to collecting institutions which often value abundance at whatever cost, The Halide Project seems to be listening to and focusing on artists and their processes, while paying special attention to their specific community needs. “[People] want to slow down,” Dale said to me at the conclusion of our interview as we spoke about the resurgence of analog processes and our collective post-pandemic needs, “They want a little bit [of] that slow, meticulous process that film photography or alt-pro has.”

Honestly, same.

You can find more about the Halide Project at TheHalideProject.org.